social science methodology: endless variations?

post 2 of 100 for the #100DaysToOffload challenge

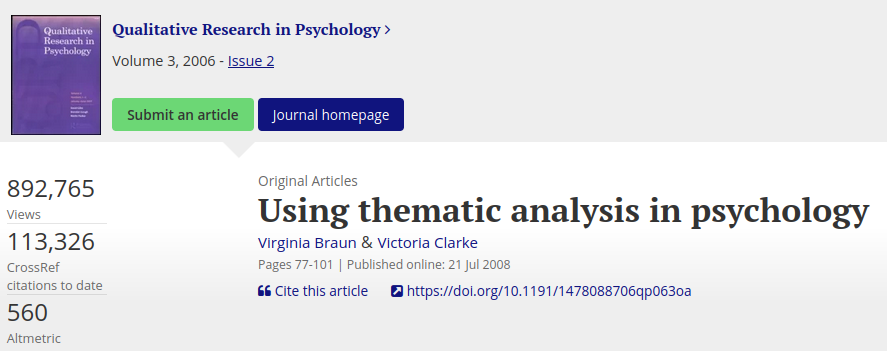

one of the most cited research papers of all time is Braun and Clarke (2006) "Using thematic analysis in psychology". at least as a UK PhD student working with qualitative data, i'd have to be stubborn, short-sighted or inept to remain unaware of it.

Victoria Clarke is also based at my institution. perhaps social researchers here are even more aware of her work than folks at other institutions, because of the influence of local celebrity.

there is a lot to say about this paper, and the phenomenon of its success. perhaps others have already said it; i haven't searched yet. but i can talk about the key takeaways and legacy in a later post. for today i want to reflect on a claim made in the paper:

Qualitative analytic methods can be roughly divided into two camps. Within the first, there are those tied to, or stemming from, a particular theoretical or epistemological position. [...] Second, there are methods that are essentially independent of theory and epistemology, and can be applied across a range of theoretical and epistemological approaches.

—Braun and Clarke 2006, p.78

the authors anchor the merits of thematic analysis, i.e. the method they're defining, in the "flexibility" of its "theoretical freedom".1

but: it's possible to disagree with their claim that some methods are inextricably connected to particular theoretical/epistemological positions. and then this relative advantage of thematic analysis vanishes.

my hunch is that you can claim almost any ontological and epistemological position and employ almost any methods. why? some initial ideas (to be tested)...

- doing research is a practice, a doing, and there isn't necessarily a link between what i say and what i do. things involved can be done regardless of your consciously-held or articulated philosophy.2 if there is a link, it is typically weak or indirect. maybe in support of this:

- we can be incoherent or wrong in our beliefs and explanations about our actions.

- at a basic level, when sending an email or asking a person a question, there is little or no influence of theory or epistemology.3 there is just action, or interaction.

- yes, some methods may be historically associated with some research philosophies or epistemologies, because they originated in a certain discipline or field. and some methods (like interpretive phenomenological analysis) may still be predominantly associated with a particular field (and thus, a dominant philosophical orientation).

- Braun and Clarke (2006) recognise this (when they say "stemming from", in the quotation given above; see also pages 80-81 in particular).

- but! this has nothing to do with the strong form of their argument, that some methods are in some way essentially "tied to" particular philosophical positions.

- methods arising in certain places is just... historical contingency. and methods persisting in some places, or being more widely adopted, is also contingent on social and intellectual processes. these facts can't support the essential alignment argument.

- the quality of coherence between philosophy and methods is the property of an argument or research design as representation, as artefact. it's not the same thing as the actual doing of the research. and we only have access to written reporting of research design and results; we can't glimpse how others' research was actually conducted. so when we debate philosophy-method fit we are doing it abstractly, theoretically.

ok. it was good to articulate that! a first draft, a hypothesis generation, for my position on the relationship between philosophy and my methods.

next steps:

- get clearer on the arguments and implications. for instance, if the strong version of Braun and Clarke (2006) is that some methods don't make sense associated with certain epistemological positions, then we should be able to articulate why and find instances where research is ~fatally flawed because of it. but i don't know what that might look like right now.

- as a UWE phd friend pointed out - Braun and Clarke's 2021 book updates their thinking from the 2006 paper. so i have to check that. from my initial skim, i did see them maintaining that their brand of thematic analysis ("reflexive" thematic analysis) is only appropriate within certain "paradigms", which seems to indicate some continuity with their 2006 position in this case.

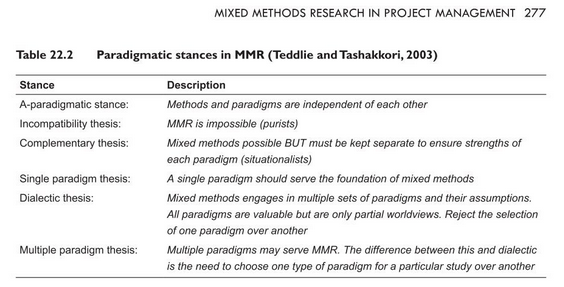

- look at mixed methods research design literature (starting with Tashakkori and Teddlie 2003, 2010). Pasian (2010) pointed me towards Tashakkori and Teddlie (2003) summarising different perspectives on this issue, including an "a-paradigmatic stance" which holds that "methods and paradigms are independent of each other". so i'm not alone here!

in the meantime - what do you think?

i'm keen to be challenged, particularly by people who have concluded they are broadly aligned with a particular -ism (e.g. postpositivist, critical realist, constructivist), and have reasoned through why that means certain methods are inappropriate for them.4

do you think there are some methods that only make sense if you have a certain philosophical position? if so, which (and why)?

- cynically, this could be a contributing factor to the article's success: a safe, even lazy, reference for any qualitative researcher to cite without fear of incoherence with any claimed ontological and epistemological assumptions.

- i catch myself wanting to use these terms somewhat interchangeably: theory, philosophy, ideology, theoretical position, ontology and epistemology, paradigm. and you can throw more into the soup, like (theoretical) framework and assumptions. differentiating these terms will make a good future post.

- practically no influence in the minutiae of my actions. perhaps there is a small influence but it is marginal, small enough to be considered effectively 0. perhaps, before the moment of acting, the menu of actions available to me was shaped by my philosophical commitments. but claiming that "there are historically or culturally typical methods for typical philosophical positions" isn't the same as claiming that "different philosophical positions modify the implementation of methods such that they are performed qualitatively differently"

- i suspect it isn't really about the ontology and epistemology though but something else, like values or questions and phenomena of interest.

References

Richard Van Noorden (2025). These are the most-cited research papers of all time. Nature 640(8059).

Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-10.

Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke (2021). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide.

Roslyn Cameron and Shankar Sankaran (2015). Mixed Methods Research in Project Management. In Beverly Pasian ed. Designs, Methods and Practices for Research of Project Management. Routledge.

Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddlie (2003). Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioural sciences. In Tashakkori and Teddlie eds. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research (first edition).

Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddlie, eds. (2010). Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research (second edition).